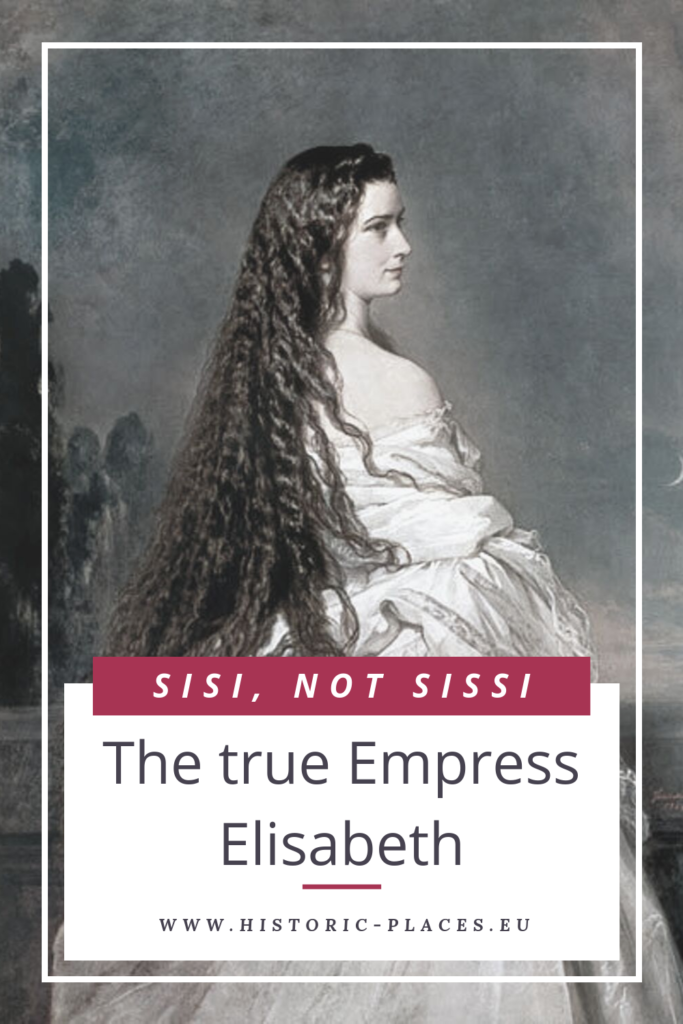

Everyone knows the films of the “Sissi” trilogy with Romy Schneider. Every Christmas at the latest, the lovely face of the young Empress flickers across the television screens. She became the ideal image of a fairytale princess for generations.

But was she even close to it?

When the historian Brigitte Hamann discovered the diaries of the Empress Elisabeth of Austria in the Swiss Federal Archives, the true Empress Elisabeth came to light. And the truth had very little to do with the film’s Sissi. Sisi, as her real nickname was, was unhappy with her existence as an empress, yes. And she was imposed far too much of a burden far too young. However, Sisi was not only a victim. She was an egocentric rebel.

From Sisi to Empress Elisabeth

Sisi was born in 1837 as Elisabeth Amalie Eugenie, Duchess in Bavaria as the fourth child of Duke Max Joseph in Bavaria and his wife Princess Ludovika. Her mother was the daughter of the Bavarian king and her father an unconventional but very wealthy man. Both had no obligations at court, so their lives were largely left to them. Sisi and her siblings grew up in the Herzog-Max-Palais in Munich and spent the summer months in Possenhofen Castle on Lake Starnberg. Sisi had little interest in her education, and she was certainly not interested in sitting still. Due to her free-spirited father, her upbringing was not strict, and Sisi and her siblings grew up rather undisciplined and informal.

When Sisi was 15, the 23-year-old Emperor Franz Joseph of Austria was looking for a bride. Franz Joseph was Sisi’s cousin, his mother Archduchess Sophie the sister of Sisi’s mother. Sisi’s older sister Helene was actually intended for the emperor, but when Franz Joseph met both girls in Bad Ischl he liked Sisi better. Sisi’s mother commented on this to the frightened daughter with “The Emperor of Austria is not turned down.”.

At that time, before her marriage, Sisi was not yet a beauty. She was a frightened girl who spoke with a Bavarian accent and was in no way prepared for life at court. When she moved to Vienna, she was sitting in her magnificent carriage, crying her eyes out. The wedding took place on April 24, 1854.

“I woke up in a dungeon, and shackles are on my hand.” So Sisi herself wrote in a poem about the following time at the Viennese court. Her husband was busy with matters of state, and her mother-in-law now wanted to catch up on her education, which Sisi lacked. This did not work well. The court looked down on the clumsy girl, and she was hopelessly overwhelmed with the demands placed on her. She began to tremble when someone came too close to her. She also hated to be shown off and gaped at. During her first pregnancy, her mother-in-law dragged her into the royal garden so that the people could see her belly. For that alone was her task after all: to give birth to heirs.

After giving birth to two girls and the longed-for heir to the throne, and after her eldest daughter had died at the age of two, this stroke of fate, her misfortune, and the ongoing loneliness and isolation at court took their toll on Sisi’s health. She suffered from constant coughing, and the imperial doctors feared lung consumption (tuberculosis). In addition, Sisi, who probably already suffered from anorexia, hungered down to a life-threatening low weight. When the court gossip accused Franz Joseph of having an affair, Sisi fled the court and travelled to Possenhofen for the first time after her marriage. The scandal was covered up.

After Sisi had been convinced to return to Vienna, she was immediately seriously ill again. This time she insisted on recovering far from the court, on the island of Madeira. Since her life was in danger, she was given in. But she fell ill again as soon as she returned to Vienna. So she turned her back on the court again, this time to Corfu. She left her two children behind again.

Body cult

When Sisi returned to the court after an absence of two years, her beauty had blossomed, as had her self-confidence. Then Sisi realized that her beauty gave her power and enabled her to fight for freedom. From then on her beauty became the center of her life.

With a height of 1.72 m, a weight of less than 50 kg and a waist circumference of 48 cm, Sisi was severely underweight. She made slenderness fashionable at the European royal courts. Dieting, riding and hours of violent marches helped her to maintain her shape. She also had her own fitness rooms set up in all the imperial palaces, where she did gymnastics and trained on equipment.

Sisi spends many hours every day with her beauty program. Overnight she laid raw veal on her face to preserve the youth of her skin. The washing of her very long hair occupied her entire entourage for a whole day. Fortunately this only took place every three weeks…

Closely linked to her obsession with beauty, Sisi was also eager to stay young forever. After she was 31 years old, she refused to be photographed and always had a fan at hand to cover her face.

Rebel

It was only when her six-year-old son Rudolf threatened to break at the hard military drill that was to make the heir to the throne a man that Sisi acted for someone other than herself. Rudolf, sensitive and subtle, was not suited to be “hardened” with water cures and fright. Sisi threatened her husband to leave him if she was not allowed to control the education of her children and her own affairs. Franz Joseph gave in, and from then on Sisi simply did what she wanted. Unfortunately, this also meant that after finding new teachers for her son – who loved her very much – she left him alone again.

She rose up against the compulsions of the hated Viennese court and did everything that was frowned upon at court. She developed an interest in Hungary, the Hungarian language and culture as well as in the Hungarian freedom fighter Count Andrassy. In one of her few political actions, Sisi finally achieved reconciliation with Hungary. Franz Joseph agreed to meet Andrassy, and Sisi had a special “promise” (or leverage) for her husband: if he agreed to be crowned in Hungary, she was willing to give him another son who would one day become king of Hungary.

To this day there are rumours that the Empress had an affair with the dashing Hungarian Andrassy and that her youngest child Marie Valerie had been his. But Sisi had little interest in men and sex throughout her life, so this rumour is very probably not true.

After the coronation in Hungary, Sisi spent most of her time travelling. She more and more resembled her exuberant and narcissistic cousin Ludwig II of Bavaria and openly displayed her eccentricity. As the newest hobby she discovered riding. The best English riding instructors made her one of the best female riders of her time. But over the years her maltreated body finally refused to serve and made riding impossible. Then Greece became her new obsession. She learned New and Ancient Greek, translated Shakespeare’s plays into Modern Greek and had the Achilleion, a castle dedicated to her favourite hero Achilles, built in Corfu.

Only for her husband, whom she had left almost completely alone in the last decades of her life, did she feel compassion. So she gave him a mistress. Otherwise, the couple remained friendly and inclined and had a lively exchange of letters. Franz Joseph also visited Sisi occasionally during her stays abroad. It was only in Vienna that the Empress hardly stayed.

The end of a mystery

The death first of her cousin Ludwig II in 1886 and then of her son Rudolf by his own hand in 1889 caused her to fall completely into melancholy. She wore only black, and again and again she played with suicidal thoughts. Her life became an odyssey. At the same time Sisi avoided the public and always had fans and parasols at hand. That way nobody could see that her former beauty had suffered under her age.

In September 1898, Sisi, now 60 years old, travelled to Geneva under the pseudonym Countess Hohenems. She rejects Swiss police protection, even though Switzerland granted asylum to anarchists. But Sisi was not afraid for her life – or even to lose it. Her anonymity was not preserved, and so on September 10th the Italian anarchist Luigi Lucheni attacked the Empress and stabbed her in the heart with a thin, sharpened file. Lucheni was actually on a mission to murder the French pretender to the throne, Henri Philippe d’Orléans, but he had not come to Geneva. So chance played Sisi into his hands. For Sisi it was probably a redemption from her unhappy existence.

Sisi, a Myth

Freedom-loving, eccentric, sometimes melancholic – Sisi could not deny the legacy of the Wittelsbach family, their ancestors. She was clever and talented, she was more than just her appearance. But she didn’t make anything of her talents and was unhappy and restless all her life. She resisted the anti-democratic currents at court and promoted liberalism. But apart from her commitment to the Hungarian Compromise she did nothing to make a political difference.

Her situation was undeniably almost unbearable, especially at a young age. And the task imposed on her was far too great for her. This pressure, combined with the legacy of her ancestors, led to numerous psychological and physical problems. Today’s doctors would probably have diagnosed at least depression and anorexia (or another eating disorder) in Sisi. It is obvious that she could neither be a loving wife and mother nor a responsible national mother.

She was only a mother to her youngest daughter Marie Valerie, who was therefore also called “The Only One” behind closed doors. Her son Rudolf, in particular, would have needed a mother: he is said to have worshipped his mother. His father had always wanted a little soldier as his son, which Rudolf could never fulfill. Could more motherly love have prevented Rudolf’s fall into dissipation, depression and ultimately suicide? Hard to say, but Sisi could certainly have had more influence on her son’s development.

Posterity transfigured her into a romantic figure, making her probably the most famous Habsburg woman to this day. Every generation projected their desires on her, and today she is often treated as the “twin soul” of Prince Diana.

“The soul that understood me never existed.”